Communities around the world are now regularly experiencing extreme weather events such as drought and flooding due to climate change. The Flow Partnership, a UK-based organization, is working in India, Slovakia, and the UK to help locals be more resilient in the face of these challenges. Minni Jain is a founder and the Operations Director of The Flow Partnership, and we are thrilled that she will present at our upcoming Soil Regen Summit 2022: Farming for the Future coming up on March 15-18. (Registration for the Summit opens soon!)

In the communities where they work, The Flow Partnership (TFP) shares their expertise in Natural Catchment Measures (NCMs). These structures slow down surface water runoff to reduce soil erosion, and allow the water to infiltrate deep into the earth to recharge water tables. TFP works directly with local community members on catchment and landscape restoration projects, rather than partnering with high-level, centralized government or corporate leadership teams. As a result, community members and their traditional water practices are at the heart of each project to address flooding or desertification. One of the primary regions TFP works in is Rajasthan, India.

Bringing Water Back to Rajasthan, India

Rajasthan is the largest state in India, located in the northwest of the country. It is also one of the driest, and as a result the state is particularly vulnerable to effects of climate change. The region can expect increasingly higher surface temperatures and weather unpredictability, as well as severe and sustained periods of drought and famine.1 Since 2014, The Flow Partnership team has collaborated with dozens of village communities on planning and funding natural water catchment projects throughout eastern Rajasthan.

It Takes a Village to Build a Johad

Villagers living in Rajasthan are profoundly affected by the cascading effects of increased drought: decreasing crop yields, poverty, malnutrition, and the resulting flight of young members of the community.

Older members of these communities remember a time when water from monsoon rains was more plentiful and communities were more vibrant. During these times, traditional, community-managed water catchment ponds, known as johads, used to be plentiful. However, they were widely abandoned due, in part, to large-scale government programs that encouraged modern technology such as “tube wells” and diesel pumps. These modern techniques are expensive and are increasingly less effective due to aquifer depletion. As a result, more and more village communities are choosing to return to traditional solutions such as johads.

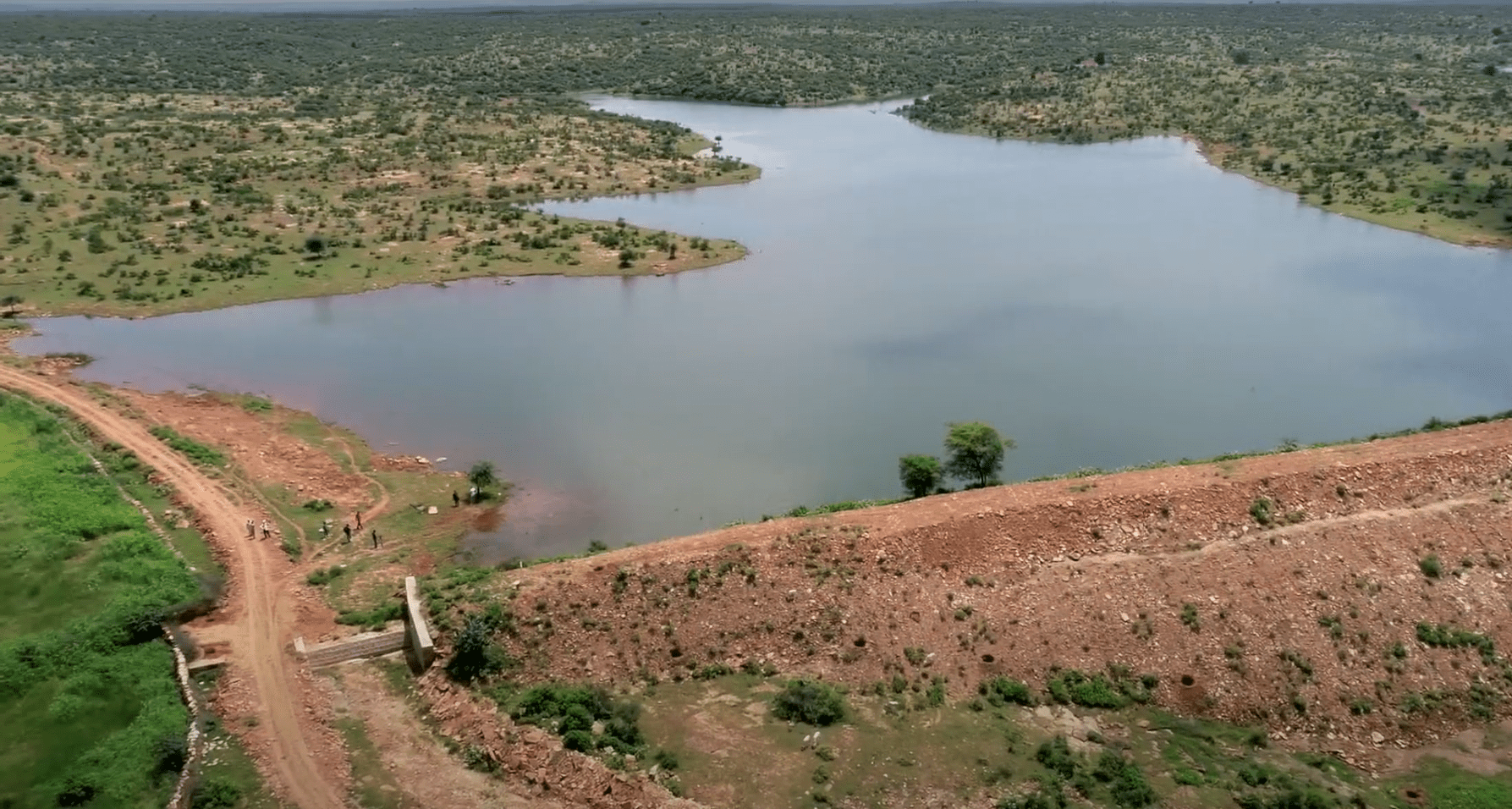

Traditional johads date back to the 1500s in India.2 They are large, crescent-shaped dams made of dirt and rock (and sometimes masonry) that are built across an existing low point in the land. These dams are placed so that the connected natural slopes form a “container” to hold rainfall and runoff. The captured water then filters slowly and deeply into the ground.

![Screen shot of a johad in Maharajpur, Rajasthan from The Flow Partnership’s “Water for All” video [YouTube, 04:44 min]](https://www.soilfoodweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/WaterForAll_TheFlowPartnership-300x160.png)

Screen shot of a johad in Maharajpur, Rajasthan from The Flow Partnership’s “Water for All” video [YouTube, 04:44 min]

How a Johad Rebuilds a Village

After a johad project is completed, the effects on the local environment are striking: erosion is reduced, aquifers are recharged, and wildlife numbers increase. The transformation of the landscape also has many positive effects in the human communities that build johads. The villages that initiate and partially fund the projects often experience intense feelings of ownership, pride, purpose, and responsibility. Their economies are also reinvigorated by introduced fish stocks in the new water bodies, better and longer-season grazing for dairy cattle, and more diverse food crops to grow and sell.

An essential improvement to communities is that young villagers can return permanently as a result of new, reliable work opportunities. Additionally, more girls in these villages are allowed to attend school regularly, since they are no longer needed to help carry water long distances. Finally, the villages with completed johad projects suffered less due to the effects of Covid because their overall health was better at the start of the pandemic.

Learn More about Johad Projects

You can see with your own eyes the positive effects of a johad project in the village of Maharajpur in The Flow Partnership’s inspiring video, Water for All. If you are interested in seeing in more detail the planning, building, and effects of a johad (as well as an appearance by Minni Jain at 04:40) in another TFP film, Johads. We look forward to hearing more about The Flow Partnership’s good work from Minni Jain at the upcoming Soil Regen Summit 2022; Farming for the Future in March!

Other TFP Projects

The Flow Partnership is involved in many other projects around the world. Take a look!

- TERI. Rajasthan State Action Plan on Climate Change Prepared for Government of Rajasthan Supported by GIZ. 2010.

- Ghoshal, D. (2015, March 23). An ancient technology is helping India’s “water man” save thousands of parched villages. Quartz. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://qz.com/india/367875/an-ancient-technology-is-helping-indias-water-man-save-thousands-of-parched-villages/

Heather Boright

Heather lives on a 4-acre homestead in the Willamette Valley of Oregon with her husband and a bunch of leafy, feathered, furry, and wooly macroorganisms. (Plus, of course, countless microorganisms.) She has a BSc in Environmental Education from Western Washington University and loves learning and writing about the science of the natural world.