Soil Food Web School’s Dr. Adam Cobb (left) and Sammie Bass (right) with Soil Nerd Anne LaForti (center) at the Radical Mycology Convergence near Portland, Oregon, USA in 2022.

A couple of us from Soil Food Web School (SFWS) recently attended Peter McCoy’s Radical Mycology Convergence (RMC) near Portland Oregon. You may recall that Peter was a speaker and panelist at our Soil Summit in March 2021 and 2022. (Watch Peter’s SRS21 presentation here). This four-day event was an awesome opportunity to spend time with 250 other fungi nerds learning about fungal partnerships and more.

We were able to connect with several current and former SFWS students, including Anne LaForti (@soilnerdalert). In fact, she facilitated an amazing seminar – one of my favorites of the entire RMC – using ideas related to fungal biomimicry based on work by Toby Herzlich of Biomimicry for Social Innovation. Anne split us into small groups to ideate about human social interactions in light of nature’s genius. In other words, what can we learn from cooperative relationships in nature?

Four Key Principles Exemplified by Fungal Partnerships

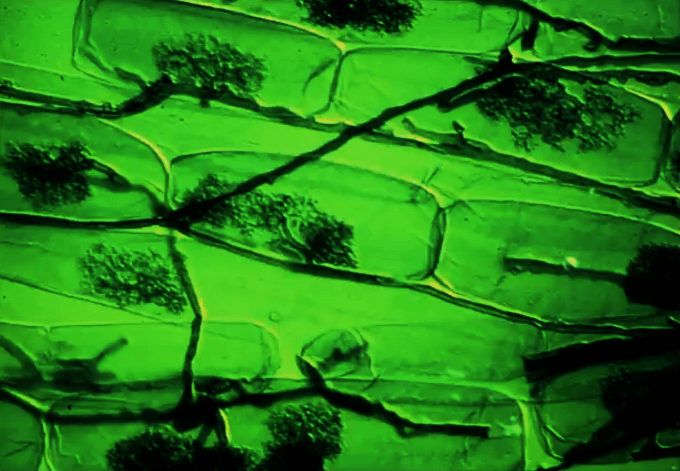

We considered symbiotic relationships involving fungi. Fungi are not the only amazing mutualists in nature, but they are involved in great examples, such as lichens and mycorrhizas. Anne LaForti’s overall concept for this seminar was to guide us through a process of reflection on the wisdom of fungal interactions and how those might apply to helping humans create a more harmonious society. Anne guided us through four principles of stable mutualistic partnerships.

- Principle One: Both organisms in an enduring partnership receive net benefits in a reinforcing feedback loop. How might we learn from this wisdom, and develop organizing principles for our interactions with each other and the natural world? So often, many of us are conditioned by culture to see our lives through a framework of competition. What if win/win scenarios are more possible than many of us typically imagine?

- Principle Two: Partners trade different resources or services. There is deep trust built into these ancient relationships, where often key life processes have been jettisoned in deep evolutionary history. For example, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi do not retain the capacity to gather carbon resources (food) from their environment because they rely on plant partners to provide for them. What if more of us were open to connection and collaboration in our local communities?

- Principle Three: Each partner organism can readily provide the resources they collect in abundance. For example, the fungal organism in a lichen community provides physical protection while the photosynthetic partner (e.g., algae) provides food. What if more human social and economic interactions reflected this principle? Would many of us find ourselves less burnt out and more enthusiastic?

- Principle Four: Partners respond and adapt to each other and their changing environments and contexts. The most consistent force in nature is change. In many ways, it is a cruel world that encourages anxiety over perceived resource scarcity. But for mutualists, their pact of community care provides a strong foundation to adapt and overcome obstacles and antagonism. What if we could relate to other humans and our planet with such trust?

We didn’t find all the answers, but we asked some important questions. We explored ideas together, at the nexus of biology, psychology, and sociology. What could be better than learning about fungi and seeking to be transformed by their billion-year-old wisdom?

Fungal Partnerships Demonstrate the Power of Diversity

For me, one of the most exciting aspects of the entire RMC was the diversity of perspectives and traditions. Herbalists, scientists, hobbyists, professionals, self-identified hippies, and on and on; in several cases, we saw within one speaker several seemingly incompatible pathways of knowledge. In fact, during one of the final presentations, the speaker, Ash Ritter (@Black.Sage.Botanicals) facilitated a wonderful group discussion about the multiple lenses that we can utilize to examine living relationships on earth.

Ash provides a number of educational videos on her website and offers herbalism consultations. Her session that day was organized around questions such as: What patterns of industrialized thinking influence how we perceive fungi and other organisms? How might we engage with plants and fungi in relationship, rather than viewing them as mere compounds and commodities?

Science, Tradition, Intuition, and Awe: Compatible Pathways to Knowledge

During her session, I mentioned how I’d heard a few speakers at the RMC express something a bit troubling to me – the idea that a scientific worldview is in opposition to many other wisdom-seeking traditions. Occasionally, speakers and panelists seemed to suggest that indigenous knowledge systems or intuition, or naturalistic philosophies are irreconcilable with science.

I shared with the group that I do not see science in conflict with insights provided by tradition, observation, personal experience, or inspiration. Just the opposite, the brilliance at the heart of most scientific discoveries is often visionary and creative! Respect and integration of ethnobotany and indigenous wisdom are important (see works by Catherine Odora Hoppers and Robin Wall Kimmerer). One of the audience members told us that in his native language the expression of the English word ‘science’ is more like, ‘the art of gaining knowledge.’ I like that!

I value scientific tools and the power of global research networks. However, the nature and character of fungal partnerships are too big to be fully understood only through a framework of scientific facts. There is poetry in fungi. There is romance in how fungi and plants help each other (see Entangled Life). The tools of science can promote our awe of these marvelous organisms, but the scientific literature cannot contain the full wonder of what they are.

Dr. Adam B. Cobb

Adam's passion for agriculture emerged in 2008, during his three months of volunteer work on organic farms in New Zealand. His time in graduate school cultivated a broad vision for the restoration of living soils, as well as utilization of research and community engagement to address current and emerging global food production challenges. After completing his doctorate at Oklahoma State University in 2016, he was funded as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow and Instructor. During the past 5 years, Adam authored or coauthored 20 research publications focused on agroecology and plant-microbial symbioses. He also taught multiple undergraduate and graduate courses on global food security, restoration ecology, and environmental science. He joined The Soil Food Web School in 2021, following his dream to help regenerate soils, improve human nutrition, and protect our planet.

I like what I’m reading. It is interesting to think about systems like these and how could people live like this. Live like what you described as Principle 4. Mutualists. Community Care. Things we all should aim for around Thanksgiving and the holidays. I’ve never commented on a blog before, I think. 🙂 Nice write up. I enjoyed it. -Jerry “the Soil Guy” Kornder

A lot of my inspiration in this subject area comes from Didi Pershouse. She is amazing, and I highly recommend you see what else she has to say: https://www.didipershouse.com/

Do beneficial fungi compete with each other? What does that look like?

Yes, they likely compete for resources and space (maybe hosts too). With increasingly limited pools of nutrients, food, water, and other resources, we typically see greater competition, even between members of the same species.