What does it mean to collaborate with nature?

In soil regeneration circles, we tend to hear the words ‘nature’ and ‘natural’ quite often. Indeed, The Soil Food Web team selected Collaborating with Nature as our 2023 Soil Summit theme. But what does the term ‘nature’ evoke? Let’s consider how it is defined in the dictionary:

“All the animals, plants, rocks, etc. in the world and all the features, forces, and processes that happen or exist independently of people, such as the weather, the sea, mountains, the production of young animals or plants, and growth.”

Is that a good definition? Is nature fundamentally independent or opposite of human influences? Who wrote that definition, and which cultural viewpoints influenced the outcome? Do humans stand apart from nature? Robin Wall Kimmerer (see podcast) does not agree, as she reflects on the inseparable bonds between humans, land, and all forms of life.

“Like other mindful practices, ecological restoration can be viewed as an act of reciprocity in which humans exercise their caregiving responsibility for the ecosystems that sustain them. We restore the land, and the land restores us”

The emergence of cooperative ecosystems

Wisdom from ancient China, as well as other philosophical traditions, suggests nature is a self-organizing system where the connections between components create a harmonious whole. This idea points toward emergence of complex interactions that transcend the abilities of individual species. Maybe that perspective can challenge humans to reimagine our organizational and social values. But, can humans be an integral part of ecosystems?

As we look across worldviews, we find many indigenous cultures do not detach humans from nature and suggest we have a valuable role to play. Should we reject human-nature dichotomies that mentally detach people from relationships with everything else on our home planet? Maybe with the term ‘collaborating’ we need to emphasize that we’re always in partnership, cooperation, and community with every tree, rock, microorganism, and one another.

Yes, our accumulated knowledge, capacity to collaborate with each other, and technologies do provide unique opportunities for humanity – we can destroy ecosystems, or we can establish a healthy connection with all forms of life around us and facilitate a thriving biosphere.

Wolves can be our teachers

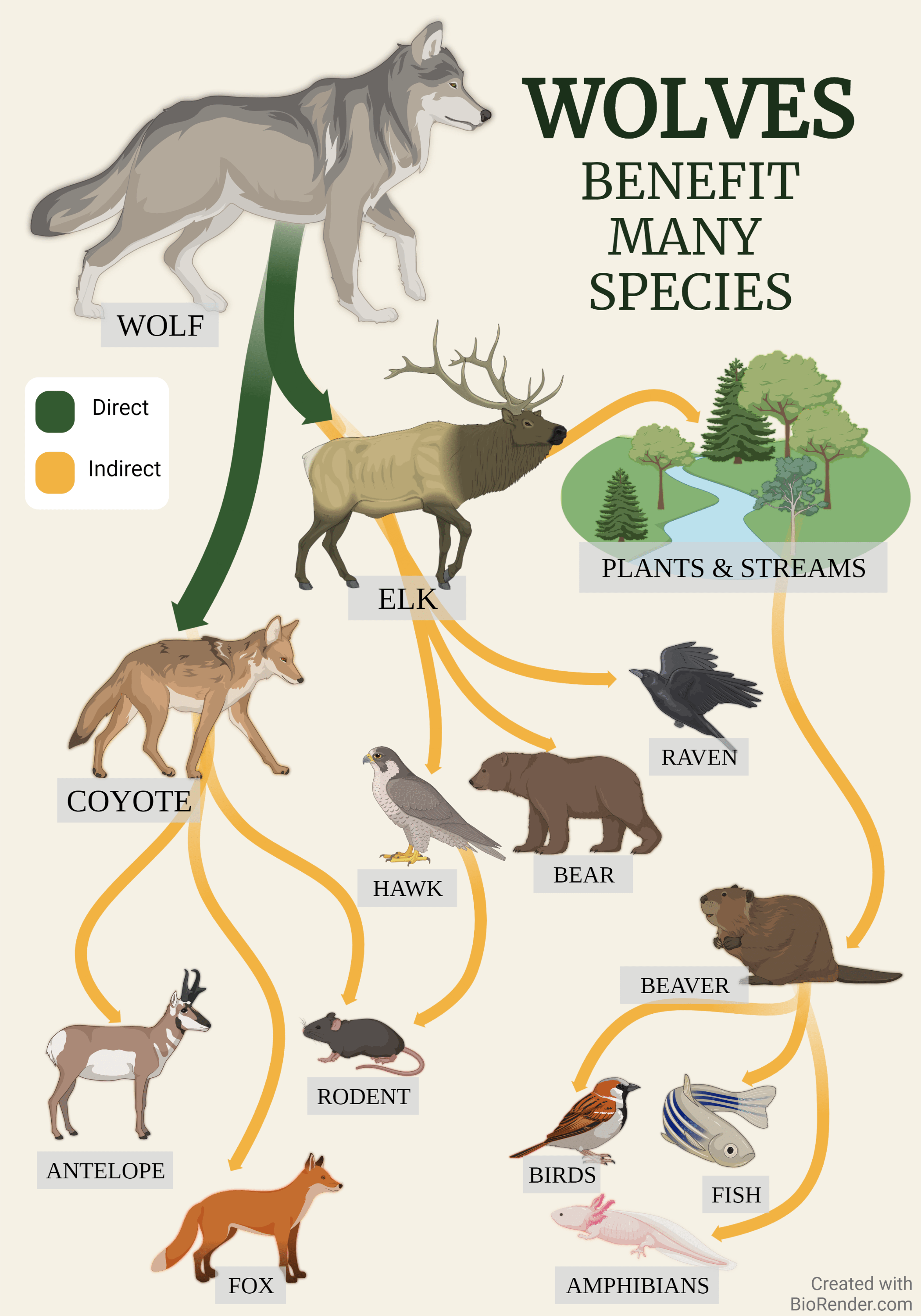

Perhaps we can look to wolves for inspiration. With their many inherent virtues, wolves can act as stewards of their environment. Wolves have seemingly unconscious habits that enhance the functions of their local ecosystems (see Figure 1). In fact, as top predators, wolves shape the behaviors and populations of many other species around them.

|

Caption: Reintroduction of gray wolves (Canis lupus) in the Yellowstone National Park had a profound impact on multiple species (direct influences shown in green and indirect influences shown in orange); these ecosystem-wide effects of top predators are often referred to as trophic cascades (see Ripple & Beschta, 2012 and Beschta & Ripple, 2019). Notably, wolves directly influence both populations and behavior of coyotes and elk, which each influence numerous other species within their area. For example, elk consume fewer small trees along river banks, resulting in greater plant production and more beaver. Beaver provide habitat to support larger populations of birds, fish, and amphibians. Species eaten by coyotes also increase, as do several species, such as bear and raven that feed on elk carcasses. |

Can we be inspired to relate to our environment more like wolves? Like us, wolves have capacities for intelligence and cooperation, yet their ecological interactions tend to create ecosystem resilience rather than overexploitation.

Opportunities for humans to support biodiversity

If we recognize the potency of our influences over our world, what individual and collective responsibilities should guide us? I can’t answer that for everyone. For myself, I’m seeking transformation of my mind and actions, cultivating greater awe and respect for every creature – great and small – and sharing my love for our living planet with anyone who will spare the time.

“Through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself. Through our ears, the universe is listening to its harmonies. We are the witnesses through which the universe becomes conscious of its glory, of its magnificence”

All of us have the ability to notice, cherish, and help reestablish living systems that self-organize. But are there voices who can lead the conversation about reconnecting human culture to earth’s ecosystems? Though currently reduced to a small percentage of the global human population, indigenous communities are guardians of global biodiversity.

Conversely, the vast majority of our human population extracts resources beyond what planetary systems can sustain. Indeed, due to the substantial accumulated harm that is directly attributed to human activities, we’ve invited speakers to this year’s Soil Summit who will challenge us to rethink our mindsets, as well as our collective social and economic practices.

The conversation continues

If our view of humans within nature leads us to greater disconnection from our membership in a holistic biological community, perhaps now is the time to shift our views. Perhaps we can remind each other to think as ‘co-creators’ with the rest of life, rather than ‘mechanical engineers’ who seek to command and control the world around us.

“But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself”

This is only the beginning of the conversation! There’s space in our community for diverse perspectives, so we hope you’ll express and represent your own personal viewpoints, especially during our upcoming Soil Summit. We’ve invited exciting speakers, such as Ash Ritter, Lyla June, and John Liu; each one has developed rich ways of expressing how humans can relate to the rest of life on Earth. We hope you’ll watch their talks and panels and participate in breakout sessions. See our full list of speakers and register for the 2023 Soil Regen Summit here.

Literature Cited

Ripple, W. J., & Beschta, R. L. (2012). Trophic cascades in Yellowstone: the first 15 years after wolf reintroduction. Biological Conservation, 145, 205-213.

Beschta, R. L., & Ripple, W. J. (2019). Can large carnivores change streams via a trophic cascade?. Ecohydrology, 12, e2048.

Author

Dr. Adam B. Cobb

Adam's passion for agriculture emerged in 2008, during his three months of volunteer work on organic farms in New Zealand. His time in graduate school cultivated a broad vision for the restoration of living soils, as well as utilization of research and community engagement to address current and emerging global food production challenges. After completing his doctorate at Oklahoma State University in 2016, he was funded as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow and Instructor. During the past 5 years, Adam authored or coauthored 20 research publications focused on agroecology and plant-microbial symbioses. He also taught multiple undergraduate and graduate courses on global food security, restoration ecology, and environmental science. He joined The Soil Food Web School in 2021, following his dream to help regenerate soils, improve human nutrition, and protect our planet.

Dr. Cobb appreciates the valuable feedback that Dr. Godschalx, Dr. Portugal, and Heather Boright graciously provided while drafting and revising this blog.

Nice article! This is also something I think a lot about. For me the key to understanding the apparent dichotomy of nature vs humanity, is to first understand that all of nature, both animate and inanimate functions as one whole living system. When we attempt to break down that whole into even two parts we automatically loose perspective. We loose wisdom in the pursuit of knowledge. Knowledge however can never replace wisdom. Wisdom is direct non referential knowing. It does not need reference points. It just knows. unfortunately we as a culture have lost the ability to trust our own innate wisdom. We search for all the answers in the form of more data. As scientists we can easily become deluded that more and more data will bring wisdom. In reality the more data we have, the more questions arise. Its like trying to squash a ball of mercury, we end up with more little balls all of which then need to be squashed. The process is infinite and we can become addicted to the pursuit of data, all the while believing we know what to do. This is the ultimate in human arrogance and if left unchecked will certainly lead to the most terrible consequences for our planet.

Perhaps if we could first learn to experience direct perception and therefore wisdom a little bit more, then our scientific endeavors would be more in harmony with the goal of working with nature and not against nature. With that approach scientific research and knowledge would serve as a means of opening up our ability to “know directly” rather than limiting the innate capacity for knowing that exists within each of us. In short we need to become “wisdom researchers” who use the scientific method as a tool to deepen our appreciation and wonder of the whole. I think in this way both wisdom and knowledge can work to benefit all beings, including ourselves.

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and

the rational mind is a faithful servant.

We have created a society that honors

the servant and has forgotten the gift”

Albert Einstein

I like what you are adding, Spero. I also have one caveat or challenge. I’m not sure “holistic thinking” is always going to present the only correct answer. It has great value, but so does “breaking systems down” in my opinion. I think of these as two different but important lenses that we need to embrace in pursuit of knowledge. It often seems like a single person “leans” in one or the other direction, and so I believe in the power of collaborative teams of diverse humans, who each bring a set of perspectives to the table. I want someone asking, “what if we think of this as one whole living system?” and I want someone else asking, “what if we zoom in on a key aspect to understand it better?”

To me, the danger is having a team that represents just one kind of thinking. For example, the “natural world” we see today is the culmination of millions of years of evolution and extinction. In fact, all the species on earth today represent a TINY sliver of all the species that previously existed but died out for various reasons (https://ourworldindata.org/mass-extinctions). It is estimated that a few times, as much as 80-90% of life was lost in a short period (most recently the cataclysm that ended the reign of the dinosaurs).

The planet is now full of life and ecosystems that assembled into what seems like stable and holistic systems, and we should study and understand them as such. Yet, when we also examine those systems for specific and highly reduced ecological and biological mechanisms, we can develop important strategies to help fix damage (often that we previously caused). This AND that – wholes AND components. This is why I tend to challenge both “sides” of any such debate. I think the most amazing things happen when we try to stitch together different worldviews!